Discrimination and stereotypes towards African-Americans still evidently exist in our society today. I have examined the discrimination that has landed upon the world of ballet and the effects thereof upon the black community in my blog posts below.

A New Era

In the 21st century, dance is starting to take a turn towards a more diverse atmosphere with more black ballerinas coming about in companies around the world. Change is starting to happen and wheels are starting to turn. Katherine Brook’s article, “17 Ballet Icons Who Are Changing The Face Of Dance Today”, highlights the recent ballet dancers who are bringing forth change in the society of dance. Some of these dancers include Misty Copeland, the third African American female soloist, and first black principal dancer at the American Ballet Theater; Shannon Harkins, the only black female in Level 7 at the Washington School of Ballet; and Aesha Ash, the first black female ballet dancer at the New York City Ballet. These ballet icons are turning around the image of “pale princesses and fair swans” and changing the face of ballet. Taking a look into the personal lives of each of these dancers, we come to find out that their success was not easy coming and the discrimination against the color of their skin still exists with the best of the best. Poppy Harlow’s article, “Misty Copeland says the ballet world still has a race problem and she wants to help fix that”, published on CNN, argues that Copeland’s presence in no way erases the ballet worlds race problem but yet exemplifies the possibility for women of color to belong in the ballet world. Even with her undeniable talent and success, Copeland explains, “There’s not a day that goes by that I feel like this is normal — or that this should’ve happened for me”. Copeland grew up in a low-income family, living in a motel with her mother and five siblings. The possibility of becoming one of the most famous ballet dancers of the 21st century was nonexistent. Along with the economic barriers, Misty Copeland discovered limitations with her body image. Copeland argues, “I have a body that a lot of white dancers have and there are white ballerinas that are principal dancers that have larger chests than me and bigger muscles and broader shoulders and they are not told they don’t belong”. She also faced criticism in her flat feet and big hair that teachers from ballet companies merely expressed as impractical. In the American Ballet Theater production of Swan Lake, Misty Copeland danced the part of the Odeile. In the typical production, Odeile does 32 fouetté turns en pointe. It is considered one of the hardest and most challenging sequences in ballet. Copeland failed to perform these turns in her performance and received an overwhelming amount of backlash on social media. Kristina Rodulfo’s article, “Misty Copeland Pirouettes on Her Haters”, published in Elle, discusses Copeland’s surprising reaction to the criticism. Instead of becoming defeated, Copeland reposted the comments and thanked everyone who pointed out her mistake. She wrote on her post, “I’m happy to share this because I will forever be a work in progress and will never stop learning. I learn from seeing myself on film and rarely get to. So thank you”. The hateful comments arise a lot of tension. Were the comments truly pointed at her mistake or her skin color?

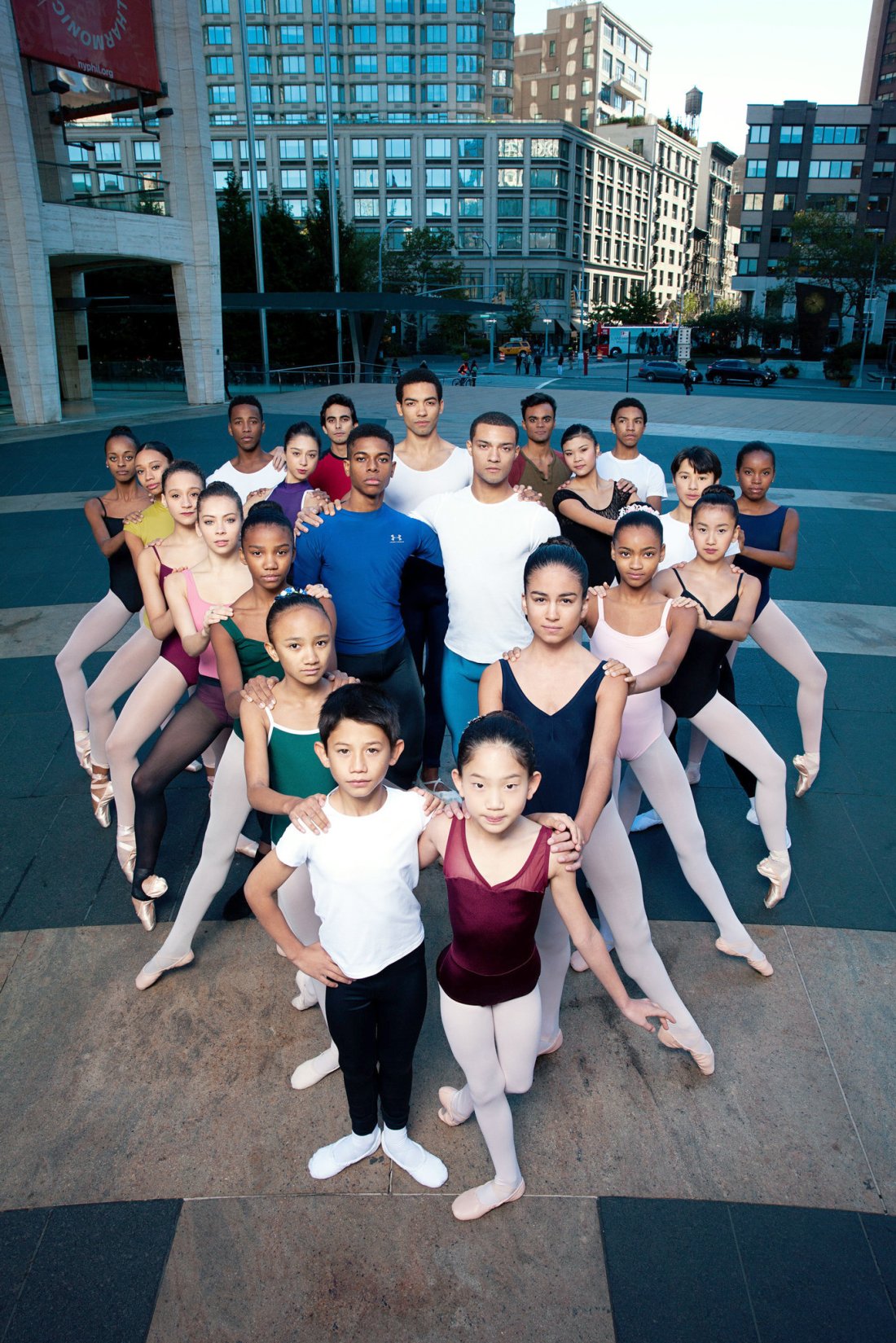

So what happens now? Gia Kourlas’ article, “Push for Diversity in Ballet Turns to Training the Next Generation”, examines the next steps that ballet companies are taking to ensure the spread of diversity. Is the ballet world really changing even in the overwhelming white presence? Kourlas argues that it is for sure changing. Organizations such as The Rockefeller Brothers Fund, the Ford Foundation, and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation are bringing in money to finance the diversity issue. Black ballerinas on stage are changing the typical audience members to people of color. Ballet Theater’s Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School and the School of American Ballet are creating programs to recruit minority groups at young ages. The ballet master of City Ballet and chairman of the School of American Ballet asserts, “We are not a white company, we don’t seek to be a black company. We don’t seek to be half and half. I just want to be American”. America has been known as the ultimate melting pot for a historically long time. The diversity that is found on American soil is vast. A Traditional American Ballet Company would mean people of all different races, backgrounds, and social classes. No more hierarchy. No more discrimination. The barriers are beginning to break. The skin color is beginning to dissolve and the focus is shifting towards the ability each dancer brings to the table. Mr. Farley, apprentice of the New York City Ballet, insists, “It’s about the particular person and about their particular gifts and the dancer’s race and their socio-economic background and their parents’ education — all of that is secondary or tertiary”. Professional companies are bringing hope to the new era of diverse ballet.

Economic Issues of Ballet

(http://www.littleballerinas.com.au/)

Dance is a very expensive career path that requires an extensive amount of training from a very young age at an extremely high price that may not be available in low-income areas. An invisible social hierarchy still lingers around the ballet world that keeps the door closed to aspiring black dancers. In the article, “Finding Solutions to Ballet’s Diversity Problem”, published on Huffington Post, writer Phil Chan offers several solutions to the dominantly white art form of ballet. He discusses the economical standpoint of ballet and the struggles that low-income families will face when trying to succeed their children through ballet. According to a study based on government data from 2009, white households make approximately 20 times the average black household makes. This rapidly decreases the possibility of black children becoming involved in ballet at a young age. Abby Abram’s article, “Raising A Ballerina Will Cost You $100,000”, published on Five Thirty Eight, examines the high price tag that is keeping ballet from being more diverse. According to her research, a top-tier ballet school training for over 15 years would (on average) cost $53,000. Of course there are less prestigious companies that dancers can train in, but still, the cost would be around $30,000. With the cost of pointe shoes averaging around $29,000 (over seven years), $2,000 on tights and leotards, and $32,000 on summer intensive camps at prestigious ballet companies, the total cost of raising a ballerina would come out to be around $100,000 to get the best possible ballet training. This total amount doesn’t even put into consideration transportation costs, physical therapy, or additional classes taken alongside ballet. That is the bare minimum. For families that are struggling to put food on the table every night, affording ballet is not even on their radar. The pool of colored dancers shrinks as the demands become more impossible to meet. Scholarships tend to be very limited and do not cover the full costs of tuition. The next issue that arises is the income after all of the endless training and outward flow of money. You would think that after all of the money spent, a ballerina would acquire much of it back to move on into the world with a nice cushion to land upon. You thought wrong. According to Jayne Thompson’s article, ““The Salaries of Ballet Dancers”, the median salary for a ballet dancer is $30,007 annually. That would cover the cost of all the 15 years of training in the least prestigious ballet school. Not only does the cost of ballet deter the colored dancer, but also the very low income after the fact.

Jane Onyanga-Omara’s article, “Classical ballet has a diversity problem and its stars know how to fix it”, discusses the different factors that exclude people of color from the art of ballet. It is very crucial to start dance at a young age if wanting to pursue a serious career in ballet. Eric Underwood, an African-American soloist in the Royal Ballet, states, “I feel that because you have to start training as a youngster, it’s the responsibility of the parents or society’s responsibility to introduce children to it”. A colored parent may not be as inspired to involve their child in ballet especially because of the white dominance over the art form. Underwood was introduced to ballet at the age of 14, a very rare occasion for such a successful dancer. Virginia Johnson, the Dance Theater of Harlem’s artistic director claims, “Blacks have been in ballet at least since the middle of the 1930s. You see the odd dancer but you see very few principal dancers”. Why is this? We are in the 21st century where boundaries are being broken and voices are being raised yet for some reason, there is still a huge lack of principal black ballerinas. A solution could be to introduce ballet to young children in low-income areas. Cassa Pancho, 38, founder of the British Company, Ballet Black, asserts that “Children and teenagers need to see someone who looks like them on stage to keep them invested in ballet”. This is where we see the never-ending, continuous cycle. There is a lack of black ballerinas, to begin with yet the process to become a colored ballerina is next to impossible. How can we fix this as a society? Many organizations have recently formed to provide scholarship money to black dancers who are pursuing ballet careers yet I believe that the problem lies deeper than this. The discrimination from the past still lingers around the ballet world. The emphasis on uniformity and ideals of what a ballerina should look like still exists. The time to change standards arrives now. Many people in the ballet community are starting to recognize this need and are taking steps to create a more accessible environment for people of all colors with institutions such as Project Plié. The lack of role models is a whole other issue but the process is slow and this is only the beginning.

The Effects of Stereotypes

(https://www.headcovers.com/wigs/) (https://www.kinkycurlycoilyme.com/ballerina-bun-on-natural-hair/)

African-Americans have been facing a whirlwind of stereotypes ever since the beginning of time that point towards the differences of their body types, including but not limited to their feet, hair, and skin color that have impacted the black performer. The Black Dancing Body written by Brenda Dixon Gottschild, an American performer, choreographer, and cultural historian who has brought attention to racism in the dance world, discusses the stereotypes of the black body and the effects discrimination has had upon the aspiring black dancer. Her discussion begins with the stereotype of black feet as “big, flat, and inarticulate” which do not coincide with the standards of ballet feet. In ballet, a high lateral arch is preferred and demanded by ballet companies across the globe; however, this aesthetic principle is merely a culturally conditioned visual that has no distinction in ability or talent. Yet, the stereotype of black feet has had such a great impact on the observers of dance that they tend to be blinded by their racial presuppositions. For example, Zane Booker, a well-known black male ballet dancer, trained and conditioned his body in the art of ballet since early childhood but still faced the area of discrimination over his black feet. Due to the fact that blacks are stereotypically believed to not possess ballet feet, a white observer looking at Booker’s feet saw not his excellently executed pointe but yet the larger stereotype of genetically non-working feet. As Gottschild points out, “it’s not always about what the (black) dancing body can do, but what the observer wants to see” (1330. The preconceived notion that ballet was off-limits for people of color has conditioned society into thinking that the black body was not genetically made for ballet.

The feet are just the beginning of the constricting beliefs of the black body. Another stereotype that has affected black women not only in the dance profession but also in everyday life, is the ignorance of black hair. Areva Martin’s article, “The Hatred of Black Hair Goes Beyond Ignorance”, published in Time, addresses the disdain and discrimination towards black hair. According to Martin, “in the 18th century, British colonists believed African hair to be closer to sheep wool than human hair, setting the precedent that white hair is preferable, a racially charged notion in and of itself”. From then until now, black women have straightened their hair in order to fit in with the norm of silky, smooth hair that is publicized in every shampoo commercial. In 2015, the young actress, Zendaya faced scorn towards her dreadlocks at the Oscars with comments about the smell of “weed” and “patchouli” from Fashion Police host, Giuliana Rancic. The disdainful comments towards black hairstyles aren’t the only issue. Many new policies have been passed in different organizations that ban the black natural hair. For example, in March of 2014, the U.S. Army issued a new policy that banned traditional black hairstyles, including cornrows, twists, and dreadlocks. The regulations even described these styles as “unkempt” and “matted.” This issue has affected the dance world immensely. At one point in time, Alvin Ailey and the Dance Theater of Harlem also banned braids, locks, and twists. Gottschild argues, “Were these economic, cultural, artistic, or inferiority-complex considerations? (213). This is where the bun dilemma was born. For ballet, the standard hair requirement is a slicked-back bun with no flyaways or bumps in sight. Black hair is not easily put into a slick bun, it must be grown out long and potentially straightened to look like the white girls. The question arises: are blacks faced with a microaggression in ballet when it comes to their hair?

The next issue that I want to cover is the conundrum of skin color. In the Huffpost article, “Study Reveals The Unconscious Bias Towards Dark Skin People We Already Knew Existed” the social problem of dark-skinned discrimination is tested in a study conducted by San Francisco State University. In the study, students were shown two words- “ignorant” and “educated”- followed by a photo of a black man’s face. They were shown the same man’s face with varying skin tones- from dark to light. After being shown these photos, the students were asked to identify which man coincided with which word. The results showed students who were shown the word “educated” often chose the photos with a lighter skin-tone when asked to recall the face they originally saw, even when the correct answer linked with the darker skinned man. The study confirmed the preconceived stereotype against dark-skinned blacks. Gottschild asserts, “Skin is the alpha and omega of racial difference. The darker the skin, the more likely will its inhabitant be excluded from white power and privilege” (190). In the performance world, the dilemma of the black smile emerged in the early years of blackface. Louis Armstrong, an iconic jazz artist from the 20th century, smiled and laughed a lot between the use of his trumpet. In doing so, he was characterized as a “minstrel-like representation of blackness” due to his white teeth, full lips, and dark skin. Another example of ill-mannered discrimination from Gottschild’s research was from a white review of a Dance Theater of Harlem performance in the 1980s. The white dance critic commented on the inappropriate “grinning” on stage, however, the dancers weren’t necessarily grinning, but for the white critic whose norm is white skin, every black smile “runs the risk of being seen as a grin” (192). This highlights yet another deep-rooted stereotype that hinders the black community. The issue doesn’t lie in the black dancing body, but in the eyes of the observer (specifically white).

Gottschild, Brenda Dixon. “Mapping The Territories.” The Black Dancing Body. Palgrave Macmillan, 2003, pp. 102-219.

Image of the Ballerina

(https://www.discountdance.com/dancewear/style_SD16.html) (https://www.zarely.co/products/z2-perform-compete-performance-ballet-tights?variant=27541691207)

Ballet is a very tough career that comes along with a very strict code of appearances and abilities. Angela Pickard’s academic journal, “Ballet Body Belief: perceptions of an ideal ballet body from young ballet dancers”, addresses the exemplary body sought after by all ballerinas and beyond. The aesthetic for “almost skeletal, hyper-flexible, ephemeral bodies” has grown in the common audiences of “predominantly white, middle-class women” (Pickard 7). The image of the prima ballerina with white pearly skin, pink tights, and beautiful lines has existed in society since the creation of George Balanchine’s perfect ballerina. George Balanchine was a Russian choreographer and dancer who brought ballet to The United States in the 1900’s. He created the School of American Ballet to train his own dancers in the image that he so desired. Jennifer Dunning’s article, “The Creation of the Balanchine Ballerina”, published in the New York Times, discusses the journey of Kyra Nichols, a ballerina in the New York City Ballet during the rise of Balanchine, and her differences from the typical Balanchine ballerina. The Balanchine stereotype was that of a young girl with a small head, long legs and exceptionally thin. This ideal has spread throughout centuries into today’s society. These stereotypes do not necessarily exclude any certain person but yet go alongside the serious training and athletic abilities in ballet. Mr. Balanchine was known to work with all different types of dancers but required them to be well-trained, have nice bodies, musicality, and excellent technique. The question that arises is why was (and still is) the ideal ballerina white and where are the black ballerinas? To look into this phenomenon, we must glance at the history and origin of ballet itself. Gretchen Schmid’s article, “The Art of Power: How Louis XIV Ruled France … With Ballet”, explores the history of ballet and the impact it had on Europe. Ballet originated in Italy and was brought to France in the 15th century by Catherine de Medici; however, Louis XIV was the one who really pushed ballet higher up in the realm of importance. During this time, the royal court were the only ones who could access the training and technique of ballet as it became one of the most important social functions of the court. Since the courts were filled with predominantly white males, people of color truly had no introduction to the art of ballet which has had an impact upon up the lack of black ballerinas across the historical context of dance.

The body standards that have held high to this day make the ballet world a very hard one to enter. Pickard’s journal examines the vast effects the standards have put upon aspiring ballerinas. Many dancers struggle with anorexia and bulimia as they try and achieve the most perfect body type for the profession. Yet when African Americans see the white ballerina plastered around social media, how is it even possible for them to achieve their look? Stacia L. Brown’s article, “Where are the Black Ballerinas?”, published on the Washington Post, addresses the issue in the lack of diversity within the ballet community. Michaela DePrince, a dark-skinned ballerina who debuted in the documentary, First Position, argues, “As a black ballerina, racism is less about what happens to you and more about what doesn’t happen to you”. As a medium of inspiration for young girls, the lack of current black ballerinas diminishes the drive to start a new generation of color in ballet. Another obstacle aspiring black ballerinas face are the costumes and everyday garments that are created solely for the white ballerina including peach colored ballet slippers and nude colored tights. The HuffPost article, “Why Are There So Few Black Ballet Dancers?” , evaluates the inconspicuous discrimination that exists in the ballet world. White skin is (and has been) the uniform for ballet. Although it can be argued that the reason there is a lack of black ballerinas is due to the fact that black children are not interested in the subject and never come to a studio in the first place, the ballet world has literally created a norm for white children to be involved in ballet and discouraged the African-American interest. The American Ballet Theater has had only three black ballerinas since its inception in 1937 and out of the English National Ballet corps 64 dancers, only 2 of them are black (2016 statistics). Luke Jennings, an acclaimed dance critic, claims, “there is not a single director of a UK ballet company who wouldn’t jump at a talented black or mixed-race dancer”. Yet do we know that this is true? Or is discrimination still running deep within the ballet world? For a black woman to dance as the black swan with any ballet company would be a world renown event. Yet why hasn’t this occurred in the 21st century? Is society still hung up on the ideal ballerina from Balanchine’s reign or is there room for the colored ballerina to take over?